Generalized "value" types and prototypal operation for C++ objects

This article is a followup to the series on interoperability and reflection. It covers extending our data model so that dataflow nodes can interoperate with not only basic types such as floats, doubles, etc. but also with more complex data models, in order to enable advanced data processing pipelines.

It also introduces a few new objects and change in ossia score that leverage these low-level improvements to enable to write nice data processing pipelines with a small reimplementation of the jq expression language.

Problem position

For instance, today one can write a simple Avendish plug-in with ports which are ints, floats, strings, bools, etc. This covers many use cases in media art systems. What happens when one wants to interoperate with, say, Javascript code which may return complex nested objects? How can we handle dataflow processors whose output is fundamentally non-trivial, such as a live feature recognizer outputting a list of objects recognized in a given camera frame:

[

{ type: "flower", rect: [0, 0, 20, 50] },

{ type: "person", rect: [100, 150, 200, 180] }

]

TL;DR: The good news is that it now works, too! That is, an Avendish plug-in can now have the following port type which is a sink for recognized objects by some ML toolkit, e.g. a YOLOvX algorithm:

struct recognized_object {

std::string type;

std::array<float, 4> rect;

};

struct {

struct {

std::vector<recognized_object> value;

} recognizer;

} inputs;

and any “compatible” input will be magically converted ; this means that even complex dataflow objects just need to speak roughly the same protocol to be interoperable, but not necessarily to use the exact same types, which allows to develop compatible libraries without requiring everyone to include gigantic base libraries such as OpenCV & the likes.

More precisely: where today one writing a PureData object would have to implement the “serialization / deserialization” protocol from PureData by hand by checking that the user’s types indeed match the types of the object’s internal data structures, now Avendish can automate that entirely.

There is a small friction point: many creative coding environments have a list type, but not all of them have a “dict” / “object” / “map” / associative container type. In particular, OSC (Open Sound Control, a fairly common network protocol in media art) itself is a sort-of-dictionary, but does not really have a way to represent dictionaries as OSC values.

Another one is that these environments generally have very, very, weak typing rule; many of our users in ossia expect the following to hold: 1.25 == "1.25".

Aggregate member name reflection

Sadly, C++ does not have enough reflection to enable us to retrieve field names from aggregates. Thus, by default, they will get converted into lists:

struct agg

{ int a = 123, b = 456; }

will be converted into [123, 456]. If one wants { a: 123, b: 456 } the field names have to be specified by hand until C++ evolves a bit:

struct agg

{

int a = 123, b = 456;

static consteval auto field_names() { return std::array{"a", "b"}; }

};

Compatible types

Most types that conform to a subset of the std:: concepts for, say, containers, e.g. SequenceContainer or AssociativeContainer should work. In my tests I mainly tried std:: and boost::container::, please report issues with any other container library! Even funkier stuff such as std::bitset works :-)

static_assert(avnd::set_ish<std::set<int>>);

static_assert(avnd::set_ish<std::unordered_set<int>>);

static_assert(avnd::set_ish<boost::container::flat_set<int>>);

static_assert(avnd::map_ish<std::map<int, int>>);

static_assert(avnd::map_ish<std::unordered_map<int, int>>);

static_assert(avnd::map_ish<boost::container::flat_map<int, int>>);

Here are some complete test cases to get an idea of what works.

Value types?

The title of this article mentions “value” types. This is not about the common C++ concept (an int is a value type) but about types that are literally called “value”.

You likely have encountered a few of those in various codebases. They tend to look like this:

using value = variant<double, string, list, dict>;

In older systems, the variant may have been implemented through ways other than templates, e.g. Qt’s QVariant, Poco’s Poco::Dynamic::Var, OpenFrameworks’s ofParameter::Value.

Here are a few excerpts of current codebases, to show the extent of the pattern:

using Value = Variant<double, bool, Object*>;

using Value = variant<int, double, bool, std::string>;

using value_base = util::variant<value_null, value_bool,

value_integer, value_double, value_unicode_string>;

using Value = mpark::variant<

PDFNull, bool, int, double, PDFName, PDFStream,

PDFIndirectObject, PDFObjectRef, PDFOperator,

std::string, std::unique_ptr<PDFArray>, std::unique_ptr<PDFDict>

>;

using Value =

std::variant<bool, uint8_t, int16_t, uint16_t, int32_t, uint32_t, int64_t,

uint64_t, double, std::string, std::vector<uint8_t>>;

using Value = std::variant<bool, uint8_t, int16_t, uint16_t, int32_t, uint32_t, int64_t, uint64_t, double, std::string>;

using value =

std::variant<number, string_val, boolean,

std::unique_ptr<table>, std::unique_ptr<list>>;

opencomputeproject/HWMgmt-MegaRAC-OpenEdition

using Value = std::variant<bool, std::string>;

using Value = std::variant<std::string, bool, long long>;

etc etc… this is only from the first page of the Github code search ; to say that the pattern is pervasive is an understatement.

It’s of course also used in ossia, ossia::value is the central type of the entire system.

The sad thing is, all these types are pretty much always entirely incompatible between them. Something as simple as

std::variant<int, bool> a;

std::variant<bool, int> b;

a = b;

does not compile because even if a and b are semantically… pretty close, they are in fact entirely different types. So something such as:

std::variant<double, std::string> a;

std::variant<bool, int, float> b;

a = b;

still doing more-or-less meaningful conversions (one could define this as “conversions that loose as few bits of information as possible”) between the types of a and b is entirely uncharted territory at least from the point of view of the C++ language’s standard facilities :-)

This all leads to another reinventing-the-wheel drama such as the one we have already mentioned in previous articles: an algorithm that uses “value” type A will have to be rewritten to work with “value” type B, even if these types are compatible, unless one is ready to turn the entire code into generic code which causes its own set of issues.

Value type support in Avendish

Very simply put, this works too :-)

Here is a complete example test-case that we use: TestAggregate is the static type defined both as input and output of the object, simply to make sure that both input and output of arbitrary types work correctly.

struct Aggregate

{

static consteval auto name() { return "Aggregate Input"; }

static consteval auto c_name() { return "avnd_aggregate"; }

static consteval auto uuid() { return "a66648f4-85d9-46dc-9a11-0b8dc700e1af"; }

struct TestAggregate

{

int a, b;

float c;

struct

{

std::vector<float> a;

std::string b;

std::array<bool, 4> c;

} sub;

using variant_t = std::variant<int, std::string>;

variant_t var;

std::vector<variant_t> varlist;

std::map<std::string, variant_t> varmap;

};

struct

{

struct

{

static consteval auto name() { return "In"; }

TestAggregate value;

} agg;

} inputs;

struct

{

struct

{

static consteval auto name() { return "Out"; }

TestAggregate value;

} agg;

} outputs;

void operator()() { outputs.agg.value = inputs.agg.value; }

};

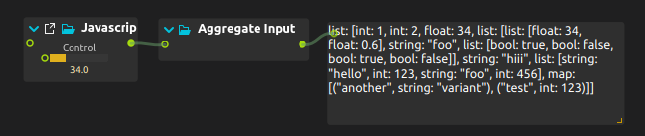

A simple JS script can be used from score for testing that this works correctly:

import Score 1.0

Script {

ValueOutlet { id: out1 }

FloatSlider { id: sl; min: 10; max: 100; }

tick: function(token, state) {

out1.value = [

1,

2,

sl.value,

[

[ sl.value, 0.6 ],

"foo",

[ true, false, true, false ]

],

"hiii",

["hello", 123, "foo", 456],

{ "test": 123, "another": "variant"}

];

}

}

This gives us the expected output, without us having to write any explicit serialization / deserialization code, thanks to the magic powers of Boost.PFR and C++20 concepts:

jk: jq for any object

In order to manipulate this kind of data easily at run-time without having to resort to a full-blown very slow JS interpreter, I decided to reimplement a subset of an extremely useful tool for working with JSON-structured data: jq. The object in score is called Object Filter ; the meat of the expression language parsing is done in the jk repository.

One can appreciate that the actual parser fits in 75 lines of C++, thanks to the awesome superpowers of Boost.Spirit! The library also leverages C++ coroutines quite a bit, as they lend themselves very nicely to the kind of operations we want to do with the library, enable lazy computations, etc.

Primer of jq syntax

jq is able to process and transform JSON thanks to a very simple expression language. For instance, .foo[2:4] will iterate over the values 2 to 4 of the array foo in the following json:

{ "foo": [ 1, 3, 5, 7, 3, 5 ] }

Another example: given [ .foo[2:5][].bar ] and the JSON

{

"foo": [

{ "bar": 1 },

{ "bar": 3 },

{ "bar": 4 },

{ "bar": 2 },

{ "bar": 5 },

{ "bar": 2 }

]

}

we are going to get as output: [ 4, 2, 5 ]. This can be tried on the online playground here. Thus, the tool is extremely efficient for manipulating complex JSON-like datasets - and our internal data model in ossia score is now compatible with this!

Only a small subset of jq has been implemented so far, but it’s already enough to perform a lot of useful data transformations. The best way to check if something is supported yet is to look into the unit tests… sorry not sorry :)

Implementation

Of course, jk needs a value type too. It is defined as follows and should cover most cases:

struct value;

using string_type = config::string;

using list_type = config::vector<value>;

using map_type = config::map<string_type, value>;

using variant = config::variant<int64_t, double, bool, string_type, list_type, map_type>;

The actual types are configurable by the application using the library, in order to be able to use, say, fast hash maps, better variants than the std:: one (in ossia we mostly migrated to Boost.Variant2 for instance) or containers with custom allocators easily.

Combined with what we mentioned before, this means that the inputs and outputs of our Avendish object are simply of type jk::value and everything gets converted automatically from and to our internal ossia::value (which cannot be changed for legacy reasons), while enabling others to use the library without the dependency on libossia. This will allow making the object work in other environments, e.g. PureData when there is some time (and enough people interested in it!).

Usage

The main thing to be aware of is how the jk object will output its values. If things are enclosed in a set of square brackets, e.g. [ .foo[0], .foo[2] ], then the output of the Object Filter in ossia scor’e will be a list. If it is without square brackets, the object in ossia score will output all the values one after each other as different messages.

Treating OSC nodes as objects

A big change in libossia recently has been to remove the pretty much unused CHAR type and replace it with a MAP type (that is, a map<string, value>).

This allows us to transmit arbitrary maps / dicts / … between objects when processing a score, and more generally get very close of the JS object model which is fairly ubiquitous and well-understood nowadays.

The first use of this is to allow using a complete OSC node and not only a parameter as input of an ossia object: the children of the node will just be treated as map elements.

That is, given the following OSC tree:

OSC:/foo/bar 1.0

OSC:/foo/baz/a "hello"

OSC:/foo/baz/b "bye"

if one sets OSC:/foo in ossia score 3.1.5 as input of an object, the object will receive a data structure akin to:

{

bar: 1.0

baz: {

a: "hello",

b: "bye"

}

}

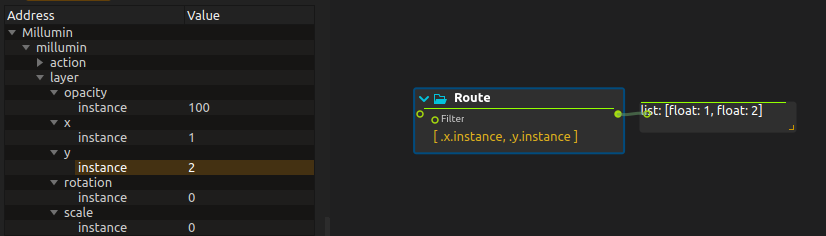

For instance, this allows to do things such as this to query specific members: in the following examples, the input of the Object Filter is set to Millumin:/millumin/layer.

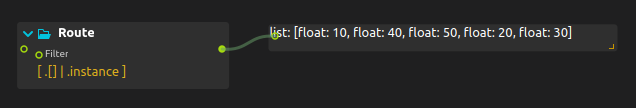

Or do it more generally like this:

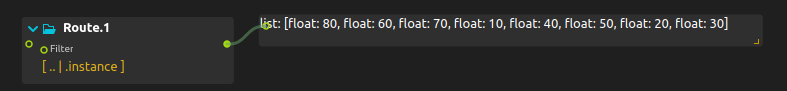

Or even recursively (in the next version as it was not implemented in time for 3.1.5):

Of course, when used as the input of a JavaScript object in score, one will get a proper JS object, which will enable much more advanced data processing!

Example

In this very simple example, we use a YOLOv4 recognizer’s raw output information to keep my side of the lab squarely into ǹ̸̙è̵̦g̷̹͒a̷̛̮t̴͚̿i̷̻̓v̴̗̎ē̶̜ ̶̩̐s̸̨̒p̴̨͛a̶̲̕c̷̢̿ë̷͈́. Now that the groundwork has been put to enable this kind of advanced objects to exist, they are going to slowly appear into further score versions.

Conclusion

Overall, the whole point of this is to allow us to transparently bridge between run-time-defined objects and transformations such as in JS or OSC, and compile-time static types to enable data processing in every way possible ; C++ objects for ossia should be able to define arbitrarily complex data structures for their inputs and outputs, and things should still be perfectly useable from the run-time environment without the end-user feeling restricted in what they can do, and with the object implementer still being able to write the cleanest code possible that solves the task at hand without having to worry about the interoperability glue code.

I think we are not far from succeeding :-) very likely a few other objects will have to be developed to simplify common use cases, but the general idea is there and held water pretty well over a few months of testing.